EPA/US NAVY/MC1 MICHAEL R. MCCORMICK

Robert McCabe, Coventry University

The upsurge of Somali piracy after 2005 led to significant international activity in the Horn of Africa. Naval missions, training programmes, capital investment and capacity building projects were among the responses to the threat. States in the region also started to focus on the dangers and opportunities associated with the sea.

Kenya and Djibouti, two states directly affected by piracy, achieved widespread reform of their domestic maritime sectors through new national initiatives and assistance from external partners. Djibouti’s President Ismail Guelleh recently commented during talks with Kenya on security and trade links that

What happens in Somalia has an immediate impact on all of us.

At its height, between 2008 and 2012, it is estimated that Somali piracy cost the Kenyan shipping industry between US$300 million and $400 million every year. This was as a result of increased costs (including insurance) and a decline in coastal tourism. It also damaged Djibouti’s maritime industry, financial sector and international trade.

The upsurge of piracy after 2005 had a number of causes. It grew from poverty and lawlessness in Somalia alongside opportunity and a low risk of getting caught. By 2013 the threat had been reduced. This was due to a combination of naval patrols, private armed guards, self defence measures on board ships and capacity building efforts ashore.

Historically, most states in the Horn of Africa have struggled with limited capacity to address maritime insecurity. Their naval assets, training, human resources, institutional and judicial structures, monitoring and surveillance have all been critically underfunded.

But the international response to piracy – and the investments and partnerships that emerged – have helped some states to improve in these areas.

More importantly perhaps, since the decline in piracy attacks, Kenya and Djibouti have been paying more attention to policies around maritime governance and “blue” economic development. This relates to sustainable use of ocean resources for economic growth, job creation and ocean ecosystem health. The refocus marks a shift from traditional investments related to land based conflict and land borders.

In a recent article, I examine how Kenya and Djibouti reformed their domestic maritime sectors following a decline in acts of piracy. The study sheds new light on the limitations and challenges facing domestic maritime sectors in Africa as well as some of the innovative approaches taken.

A key point is that blue economic growth is not possible without addressing security threats at sea. This includes building a robust maritime security sector, improving ocean health and regulating human activity at sea in a more sustainable way.

International partnerships

Many of the new developments in the region have been supported by international partners. The Djibouti Navy and Coastguard work closely with the US Navy. Together, for example, they are developing capacity for stopping and searching suspicious vessels. This is important in countering the illicit trafficking in people and smuggling of migrants through Djiboutian waters.

Djibouti has also benefited from Chinese direct investment, which accounts for nearly 40% of the funding for its major investment projects. Chinese state-owned firms have built some of Djibouti’s largest maritime related infrastructure projects. These include the Doraleh Multipurpose Port, a new railway connection between Djibouti and Addis Ababa, and the opening of China’s first foreign military facility.

This is a clear example of Beijing prioritising its growing economic and security interests in Africa. And advancing its “massive and geopolitically ambitious” Belt and Road Initiative.

Kenya, too, has received international assistance and investment. This includes support to set up the Regional Maritime Rescue Coordination Centre in Mombasa. Organisations like the International Maritime Organisation have led training for staff from the centre and for the Kenyan Navy.

The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime has provided law enforcement training for the Kenyan Maritime Police Unit. It also opened a new high-security courtroom in Shimo La Tewa, Mombasa, for cases of maritime piracy and other serious criminal offences.

National refocus

At a national level, there is evidence of a fundamental shift towards building a more secure and sustainable domestic maritime sector.

For example, Kenya has created a new coastguard service. Its job is to police the country’s ocean territory and to ensure that Kenya benefits from its water resources. The country has new naval training partnerships, maritime capacity building projects and an implementation committee to coordinate “blue economic” activities. These include fisheries, shipping, port infrastructure, tourism and environmental protection.

For its part, Djibouti has rapidly developed its maritime sector and recognised the financial benefits of leasing coastal real estate. The country has an ambitious development plan titled “Djibouti Vision 2035”. This sets out its aspiration to become a maritime hub and the “Singapore of Africa”. It’s trading on the fact that it has a similar strategic position along one of the world’s busiest shipping lanes.

All of these approaches require robust laws and regulations governing human activities at sea. They also call for a capable and flexible coastguard and navy to enforce these regulations and secure coastal waters against threats such as piracy, fisheries crime and the illicit smuggling of drugs, weapons and people.

The way forward

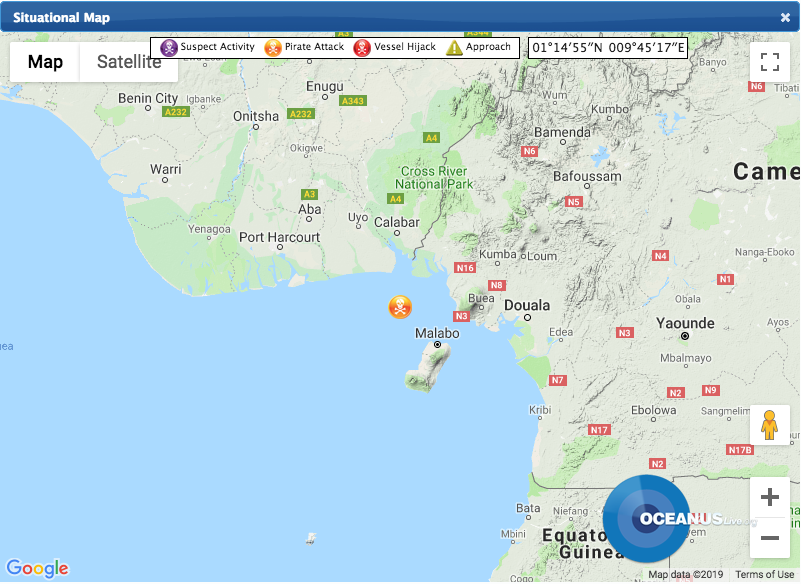

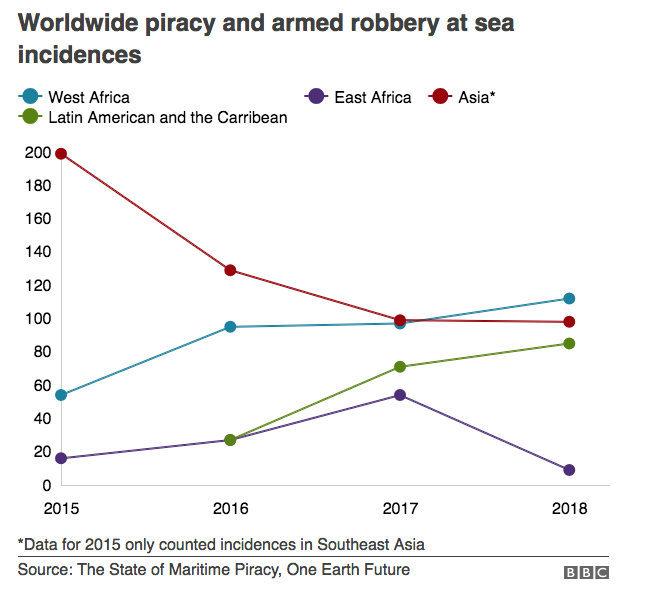

There are lessons in the Horn of Africa experience for other regions of Africa facing similar maritime insecurities. One example is the Gulf of Guinea.

The first lesson is that there’s a need to convince coastal states with weak maritime capacities of the untapped potential of the blue economy. Even reputational damage can harm tourism, development and investment in coastal regions. This was clearly illustrated in the case of Kenya.

Blue economic growth needs a safe and secure maritime environment for merchant shipping in particular. It can also help alleviate poverty in coastal regions, provide alternatives to criminal livelihoods, and allow local communities more ownership of issues that affect them.

Ultimately, maritime security and blue economic growth need to be considered as a unified policy issue.![]()

Robert McCabe, Assistant Professor, Coventry University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.